Is Fascia Really Relevant To Chronic Pain Relief?

From myofascial release, to fascial stretching therapy and fascial release tools, everyone seems to be focusing on this specific body tissue.

In this article, we're going to take a look at fascia, as it's been a rising hot topic in the alternative therapy realm, and whether or not it therapies targeted at fascia have value for the chronic pain sufferer.

What IS fascia?

In gross anatomy, fascia is simply connective tissue that wraps around muscles and other anatomical structures. If is flexible and capable of stretching in response to muscle contractions and body movements, and it covers almost every organ, not only muscle groups.

So it IS flexible enough to move along with muscle so that it won't obstruct its normal contraction.

The growing interest in fascia started by the idea that musculoskeletal pain is triggered by deformation of this connective tissue wrapping. This model of pain has been named the "Fascial Distortion Model", and was introduced in 1991 by Stephen Typaldos, but other therapists have talked about fascia in relationship to pain and musculoskeletal dysfunction over the years. Therapists such as John Barnes have been teaching myofascial release for decades.

According to the Fascial Distortion Model, it is possible to fix fascial distortion by a series of techniques involving handwork and specialized tools.

Even though it is mentioned by the American Fascial Distortion Model Association that this model has proven useful in treating acute and chronic injuries, there is no scientific validation that such distortions actually exist or that manual therapy specifically can do anything about it.

Facts about fascia you need to know

Misconceptions about fascia and how it is related to muscle pain are EVERYWHERE now, and even skilled physical therapists, chiropractors, fitness trainers, and massage therapists are lured into fascination by its assumed implications.

Somehow we are led to believe that fascial restrictions can be identified through chains or patterns throughout the body, and targeted with either stretching, hands-on techniques, or using metal tools designed to work directly with fascia.

The problem is these claims are simply not well supported by science, and most research appears to show we can't do much about fascia directly, especially not in the short-term.

This appears even more evident when we learn about the actual strength of fascia. It's pretty hard to believe any changes in extremely dense and tough tissue can be accomplished within the context of a therapy session, or even a few for that matter.

Consider the following facts:

It is NOT possible to change or deform fascia using manual therapy

A study published in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association evaluated the ability to deform or change fascia via massage therapy. This is relevant to the claim that fascial release improves pain because according to this model, therapists should be able to stretch or fix "fascial deformations" in the first place.

However, the evidence pointed out by this paper shows that mechanical deformation and stretching of fascia is only possible by using high forces (on the plantar fascia and IT band), while certain types of fascia (in the nose for example), may be influenced by less.

To put this in perspective, in order to deform the fascia on the bottom of the foot (plantar fascia) by 1%, you would need to apply more than 8,000N of force. The force of a lion's jaw can produce a bit more than 4,000N of force!

This is because this thin layer of connective tissue is too tough to lengthen by simple common clinical therapeutic techniques. The amount of pressure needed to do so would be extremely stressful (if even possible) by the therapist, and certainly be extremely painful to the recipient.

Thus, it's not likely at all that these alleged fascial distortions can be fixed by massage, or stretching techniques.

Fascial contraction and pain

Some studies show that similar to the muscles they cover, fascia can undergo a weak and slow type of contraction. This is undoubtedly exciting information and destroy the thought that fascia is form of inert connective tissue.

However, it should be stressed that contractions found in fascia are extremely subtle and difficult to register, especially when you compare them to that of muscles.

The question is whether or not there is any real significance to these contractions, especially in the context of therapeutic techniques. (Actual practice, not just in a test tube!)

Is it possible that such a weak contraction can influence the correct functioning of muscle groups?

That's a tough sell to assume that these weak contractions generated in-vitro would act by themselves in the body causing deformations to the fascia and triggering pain.

Another entertaining thought is that any manual therapy practitioner can actually assess or feel the release of fascial tissues, and be able to distinguish them from both the muscles contained, as well as all of the tissues that lay on top of them! Virtually impossible.

We haven't even touched on the issue that pain itself is not purely a structural issue. We know that tissue damage and pain are not fully associated, so even if damage to fascia is found through deformations, etc., it doesn't mean it has ANYTHING to do with pain!

The primary mechanism for pain relief lies in changes to your nervous system

I've already mentioned how tough the fascial covering of a muscle is and that is very unlikely to mold or fix fascia with manual therapy.

Doing so would require excessive pressure that is inconceivable in massage or stretch therapy.

However, there is definitely something that feels different after these heavy-pressured massage or stretching sessions, and of course many people report feeling pain relief.

Does this prove that fascia needs to be released? Does it validate the narrative often espoused by these fascia-focused therapies?

No, it doesn't prove that at all. There are a great many potential reasons why people feel better after hands-on therapy sessions.

Endorphins improve pain, novel sensory input can alter perception of pain, activating the parasympathetic aspect of the nervous system, and even the placebo effect are all potential explanations and common effects from manual therapy.

The take home point here is that we can emphasize the end result of feeling better through movement and manual therapy techniques, and get rid of the likely false story of WHY those techniques are working.

One of those false stories is that you feel better because of changes to your fascia, and how it could have been altered as an effect of the therapy.

References:

Thalhamer, C. (2018). A fundamental critique of the fascial distortion model and its application in clinical practice. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies, 22(1), 112-117.

Chaudhry, H., Schleip, R., Ji, Z., Bukiet, B., Maney, M., & Findley, T. (2008). Three-dimensional mathematical model for deformation of human fasciae in manual therapy. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 108(8), 379-390.

Schleip, R. (2003). Fascial plasticity–a new neurobiological explanation: Part 1. Journal of Bodywork and movement therapies, 7(1), 11-19.

Meltzer, K. R., Cao, T. V., Schad, J. F., King, H., Stoll, S. T., & Standley, P. R. (2010). In vitro modeling of repetitive motion injury and myofascial release. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies, 14(2), 162-171.

Schleip, R., Klingler, W., & Lehmann-Horn, F. (2006). Fascia is able to contract in a smooth muscle-like manner and thereby influence musculoskeletal mechanics. Journal of Biomechanics, 39(1), S488.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/3/120315-crocodiles-bite-force-erickson-science-plos-one-strongest/

Tags In

Sam Visnic

Most Popular Posts

Categories

- Deep Gluteal Pain Syndrome (8)

- Deltoids (2)

- Foam Rolling (2)

- Glutes (9)

- Hamstrings (5)

- Hypnosis for Pain (3)

- Lats (2)

- Levator Scapulae (4)

- Lifestyle (8)

- Massage Therapy (39)

- Mobility (21)

- Movement and Exercise (19)

- Muscles (22)

- Nutrition (2)

- Obliques (1)

- Pain (25)

- Pectorals (3)

- Piriformis (3)

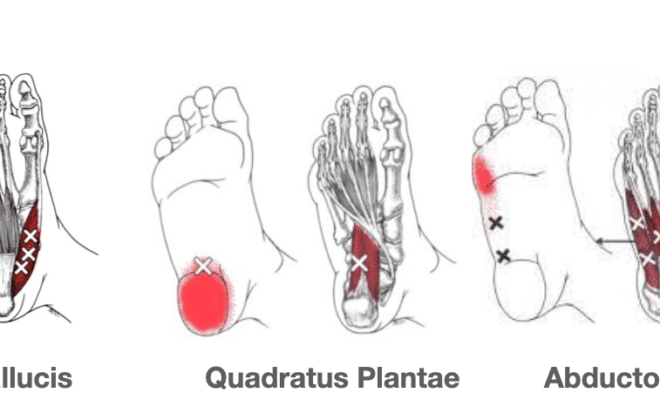

- Plantar Fasciitis (11)

- Psoas (11)

- Quadratus Lumborum (3)

- Quadriceps (2)

- Rhomboids (3)

- Sciatica (1)

- Serratus Anterior (1)

- SI Joint (14)

- Sternocleidomastoid (1)

- Stretching (18)

- Subscapularis (1)

- TMJ (2)

- Trapezius (1)

- Uncategorized (12)